Tony Gloeggler

Spaces

Since my father died

I call my mother at least

twice a week. I ask

about her day, if her feet

still hurt. I wish

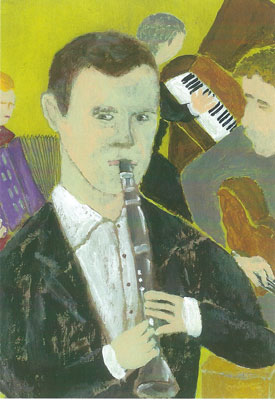

we had more to say. Jazz

plays softly on my stereo

as she tells me the new

burner was installed Thursday,

the garage door is falling

apart and the yard needs

weeding. Soon, she’ll realize

she’s talking to the wrong son.

I can balance her checkbook,

pitch batting practice

to the grandkids for hours.

But I can barely tell

the difference between a pair

of pliers and a wrench.Anytime I had to work

around the house, Dad

would end up yelling

and send me to my room,

finish the job himself.

I’d slam the door, strap

headphones on and blast

The Young Rascals. Later,

he’d push open my door,

toss me my fielder’s mitt.

We’d race the six blocks

to the sand lots. He crouched

behind home plate, put down

one finger. I tugged my cap,

started my wind up and hit

his target with a high hard oneThe Friday before Father’s

Day, I asked Mom

if she would be alright, if

she wanted me to come by.

She started to cry. I felt

helpless, tried to untangle

the extension cord. I knew

she would never tell me

what she misses most

about him, or when she feels

the loneliest. I kept

quiet, listened to the music.

Monk was playing a piece

I couldn’t name. The spaces

between the notes kept getting

bigger, and somehow I knew

Thelonius had made those places

so my mother could cry

and I could listen.(originally published in Skidrow Penthouse)

Larger Than Life

I haven’t watched a minute

of this winter’s Olympics, carefully

avoided all the flag waving, all the medal

counting. I missed the sublime skaters

and merely glanced at the headline

announcing that a Georgian luge athlete

died on a first day practice run. But I remember

that long ago summer when the gymnasts

were all thirteen and built like muscular twigs,

their bright white teeth fixed in graceless

smiles, the anointed crowd favorite,

her Stalinesque coach and her father

dying of cancer back home in Kansas.

With background strings swelling

the announcer’s reverent voice

told us about her long endless hours

of dedicated day after day training

and how she spent the last four years,

really her entire life, for this one moment.

She raised her hands high above her head

and bounded, bounced, danced, jumped,

twirled, flipped, and oh shit, slipped,

skidded and crumbled into a heap.

The crowd hushed and I couldn’t keep

myself from hoping she’d pick herself

slowly up, bravely finish her program.

Or better yet, get up girl, c’mon, start

walking and keep walking, off the mats

and through the arena’s basement, step

into the world. Go home and fall in love

with the boy next door, wear a white dress,

build an ordinary, fuller life. Maybe, a life

like mine: Scan box scores on crowded subways,

walk down tree lined Brooklyn blocks, climb

the group home’s stoop, open the door to find

my second favorite kid looking like he caught

a left hook from Mike Tyson in his prime.

Then try to figure out what happened, take

steps to make sure no one hurts Lee again.

Leave work after lunch, ride the railroad out

to Long Island, visit my brother serving time

for a DUI. Sit in an over-crowded, noisy trailer

for two hours counting other white people,

the breathlessly sexy women, their restless kids.

Get screened in, watch my brother walk

across the cafeteria, shake hands, relieved

that he looks healthy, seems in good spirits.

Can I mail him anything else? Try ignoring

all the women bending and flashing breasts,

the slow soulful kisses, the three year olds’

bouncing happily, wrapping their arms

around their daddys’ necks, giggling.

End the evening at a jazz club listening

to a fat black man play piano, make Elvis

sound like prayer and old river hymns

grind like mortal sin while I sit across

from a beautiful new woman wearing

polka dots and braids, eating barbecue.

Marianne moves closer and squeezes

my arm, laughs. I imagine more music,

darkly lit bars, sweaty rock n roll.

I lean in and find her mouth, fast forward

to her hallway, watch her skirt swirl, lift

lightly as we climb five steep flights, press

against her as she pushes the door open.(originally published in Nerve Cowboy)

Tony Gloeggler is a native of NYC and manages group homes for the developmentally disabled in Brooklyn. His books include two full length collections ONE WISH LEFT (Pavement Saw Press, 2000) which went into a second edition and THE LAST LIE (NYQ Books 2010). UNTIL THE LAST LIGHT LEAVES is forthcoming from NYQ Books.