Lost on the Blood Dark Sea and

The Ghosts and Bones of Troy

by Robert Cooperman

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Lost on the Blood-Dark Sea

Poetry

FutureCycle Press, 2020

$15.95, 96 pages

ISBN: 978-1942371946

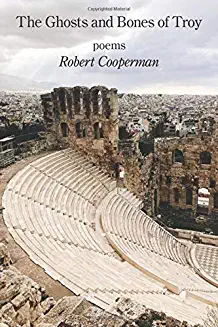

The Ghosts and Bones of Troy

Poetry

Kelsay Books, 2020

$18.50, 107 pages

978-1950462599

Robert Cooperman’s two new poetry collections are reconsiderations of Homer’s Odyssey. In Lost on the Blood-Dark Sea, the poems take on Odysseus’ adventures on his journey home, from the lotos eaters and the cyclops through the sirens, Circe, Scylla and Charybdis, etc., to his final challenge with the nymph Calypso, where he spends the final seven years, resisting Calypso’s promises of immortality if he’ll only stay with her; he is longing for Penelope and home. In a concluding villanelle, in the epilogue, finally back home, Odysseus considers his lost companions, lamenting the whole ordeal. The poem begins:

We were as good as the gods let us be,

no worse than other men who went to war:

caught by the war-madness and the blood-dark sea

Apart from a Prologue in which Odysseus kills a harmless boy, Hemnos, the night the Greeks sack Troy, The Ghosts and Bones of Troy, on the other hand, takes place after Odysseus is already home in Ithaca. Haunted by the killing of Hemnos, Odysseus suffers classic PTSD symptoms, drinks too much, disturbs his wife and family with his behavior and attitude, even contemplates suicide. While The Ghosts and Bones of Troy is about Odysseus’ return home, the trauma of the war is very much on his mind. Just as Lost on the Blood-Dark Sea concludes with a villanelle, so this collection begins with a villanelle, here in the voice of the slain Hemnos, cursing Odysseus:

May you thrash, gasping like a landed trout,

sweat, like entrails, slinking down your face and chest,

may phantom swords and spears make you cry out:

the agony real, real blood pouring in gouts.

May you never cherish an instant’s rest,

and forever thrash, gasping like a trout.

In the first collection, in the voices of Odysseus’ doomed men, most of them made up – Menardes, Lethereus, Polymenes, Partaxes and Leonides among them – we hear about horror after horror, loss after loss until the only one left living is Odysseus himself. In the adventures with the Sirens, for instance, Leonides begs Odysseus to allow him to listen to the Sirens’ song. The Sirens were nebulous beings who lured sailors to shipwreck on their rocky coasts with their enchanting singing. In paintings, they are variously depicted as monsters or as alluring, seductive women. The cover of Lost on the Blood-Dark Sea is a painting by John William Waterhouse, a 19th Century Pre-Raphaelite English painter, called “Ulises y las Sirenas,” which shows them as winged beings.

In a poem entitled, “Leonides, Bard of Ithaca, Asks to Hear the Sirens’ Song,” Odysseus is bound to the mast and allowed to listen, but he grants permission to Leonides to listen also. “‘Lord Odysseus, tie me to the mast / as well,’” the bard pleads. But in the next poem, Odysseus regrets what ultimately happened: “Poor fool, filled past the brim with a bard’s pride, / and I the stupid agent of his doom.” For Leonides is so enchanted by the Sirens’ song, he undoes his restraints and dives overboard, to his death. “He found boulders sharper than Hector’s sword, / harder than the axe that Aeneus wielded….” His death is heavy on Odysseus’ soul. Then comes a poem from the Sirens’ point of view.

We failed, not the bard we wanted, or rather

not just the bard, but this Odysseus,

alleged the cleverest man of the Greeks.

This is how Cooperman proceeds in both collections, describing an event from multiple perspectives, in the voices of a variety of characters.

The difference between Lost on the Blood-Dark Sea and The Ghosts and Bones of Troy is that while Cooperman embellishes on the stories of Odysseus’ voyage in the first, looking at the events from different angles, the events are still those that occur in Homer’s epic. In the latter collection, it’s all pretty much made up. For in The Ghosts and Bones of Troy, Odysseus is like a guy coming home from Vietnam or Iraq. He’s restless, he’s guilt-ridden. In fact, he becomes a troubling pain in the ass to his wife, his son, the whole community of Ithaca. But on the one hand, Penelope feels great love and compassion for what her husband once was, while on the other, Telemachus, their son, is flabbergasted by his current behavior. He fumes:

Mother has denied me

my birthright to rule,

as son of my once-great,

but now ruined, father,

his dreams one long shriek

of terror and guilt

to remember he slaughtered

Troy’s children.

Finally, Odysseus is exiled. It’s not simply a power play on Telemachus’ part, it is also getting rid of an imminent threat to the well-being of the larger community. Without giving away the story, Odysseus then tries frantically to redeem himself for killing the boy in Troy, while evading assassins and danger. He turns to acts of compassion. Does he succeed? The final poem in the collection is likewise in the voice of Hemnos, the child he killed.

But the larger issue in these books is the costs of war, the fool’s gold of “glory” and “heroism.” Cooperman has written elsewhere about the foolish waste that is war. Their Wars depicts the waste of even that most justifiable of all conflicts, World War II. In that collection, we see the anti-Semitism in a boot camp in the South and its tragic effects. In Draft Board Blues, we see the heartrending consequences of one of the least justifiable wars, Vietnam.

In both of the current collections, the terrible losses are likewise the main takeaway. Though he comes home a hero, all Odysseus can see in Lost on the Blood-Dark Sea is the loss of every one of his companions, for which he feels responsible. In The Bones and Ghosts of Troy Odysseus mourns in particular for the innocent, defenseless child he slaughtered, but again, it’s the overwhelming futility of bloodshed that ultimately weighs on his soul.

These books will be enjoyed for the inherent magic of the Greek myths, the adventures of the hero, as well as for Cooperman’s vivid, lyrical verse, enchanting as the stories themselves. But the impact of the underlying wisdom of these poems is likewise an enticement.