Secret Formulas & Techniques of the Masters

by Jackie Craven

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Secret Formulas & Techniques of the Masters

Poetry

Brick Road Poetry Press, 2018

$15.95, 108 pages

ISBN: 978-0-9979559-5-8

There is so much to admire about Jackie Craven’s new collection of poems, from her dazzling language to the themes of painting and gardening and family and secrecy that knit this work together. Indeed, it is the way that Secret Formulas & Techniques of the Masters is like a bravura performance, a cohesive tour de force, that is the most admirable thing of all. The title of the collection, as Craven remarks in her Notes, comes from the French painter Jacques Maroger’s 1948 book with the same title, which details the formulas used by painters like Rubens and Van Eyck and others to enhance the color and brilliance of their work – the radiance, the light and shadow – that Maroger claimed to have re-discovered. The five sections of Craven’s collection are all prefaced with quotations from Maroger’s book, themes to which the poems that follow loosely cohere. The poem, “Maroger’s Magic,” prefaces the whole collection, and indeed, this whole volume is magical. That poem begins,

The night before he left for the nursing home,

my stepfather called to tell me about the burglars

who slipped through his skylight, whisked away

the Portmeirion china, the vacuum cleaner,

and the four-poster bed – removed everything

without disturbing his blankets or his sleep.

Even your mother’s paintings, he said, the one

with the goose, and that Mexican scene, ant the still life

with the pomegranate spilling seeds so red

they’d make your tongue curl….

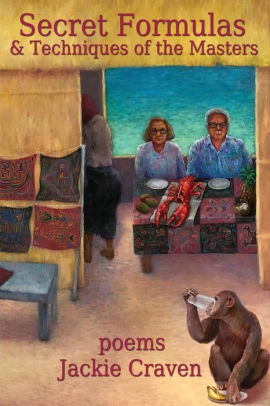

The stepfather’s slow decline into dementia is a recurring theme along with her mother’s painting –more than half a dozen of the poems are ekphrastic works involving her mother’s paintings. The cover art, in fact, is a detail from one of her mother’s paintings, which is likewise the subject of the poem, “Lobster for Lunch,” a Mexican-painting poem.

The final poem in the collection, “Stopping by the Columbarium on a Sunny Afternoon,” involves the poet visiting her parents at their final resting place. It comes from the section entitled “When the Last of Them Died,” whose Maroger epigraph reads: “When the last of them died the secret of their marvelous method disappeared.” So, in short, without being in any real way chronological, the poems trace the poet’s life within the lifespan of her parents, which gives a real pathos to the collection, as if these poems are themselves formulas to bring a family back in vivid, colorful detail.

But the theme that is most intriguing, which inevitably comes along with any consideration of one’s family, is secrets. There is something unknown and unknowable in everything we see, Craven seems to suggest. These poems are a way of shining a light on something hidden, obscure (hence the appropriate allusive quotations from Maroger, such as the epigraph to the first section, “Without light and shadows an object would make no appearance to the eye.”) “I Heard a River Downstairs” is a childhood impression that begins:

Half-formed words hissed to the surface

and tried to walk on land. Silver-scaled whispers

swished from the kitchen, fizzled

down the hall, and swelled

in my parents’ room….

One gets the impression from reading these poems that there might be something semi-scandalous in the family history, but only in the sense of a discretion the poet wants to maintain.

The poem “Killing Mr. Big,” whose very title suggests some sort of gangland scandal but whose subject is euthanizing an ancient, incontinent cat, concludes:

Mercy and expediency –

squabbling like weary lovers

who tell so many lies, keep so many secrets,

and sleep with legs entwined.

And so it is in any family, lies and secrets coiled like DNA. The gardening poem “Slugs,” from the same section, begins “Every day they quadruplefy. My mother / finds them eating her Dorothy Benedict hostas…” Later we read:

And beneath our Persian carpets? Forty years

of secrets. I should confess:

I’ve left my teaching job, driven away

a decent husband, and pursued a romance

with a woman. Mother comes in from the garden

limping from the want of new knees,

sits beside my stepfather, and ponders his ragged rows

of numbers. If I wait long enough, they’ll die

and I won’t have to tell.

The whole third section, “Colors Distinguish Themselves” (“Colors distinguish themselves clearly from one another only in the light; in passing into the shadow they grow weaker and disappear.” – Jacquez Maroger) is a nineteen-part poem entitled “Secret

Sister” (“She reached the age / of invisibility….a Marvel Comics character / caped.”). This may refer to a daughter of the stepfather who died, whom we read about in another multi-part poem, “Perspective Dreaming,” when the stepfather, in his increasing confusion, is already mixing the poet up with his son (see also “Simulcast”).

There are other, more lighthearted poems about happy hour and cocktails that evoke an earlier time straight out of Mad Men, like “Cocktails on the Patio, 1964” and “Still Life with Stuffed Olive,” even “The Absinthe Drinker.” Lest any of this sounds melancholy or maudlin, which is not the impression one gets at all from Craven’s poetry, it might be best to conclude this review with one from the section entitled “The Strength of Jelly".

Beware the Pearly Gates

Pastors dangle heaven like a pilgrim’s promise

to a trusting tribe. But, imagine the horror

of two dozen exes unfurling reproaches,

disappointed parents shaking bobbleheads,

angel ancestors tsking over silver harps.

How can there be bliss with so many people from our past

gathered like drunken relatives at Thanksgiving,

platters heaped with recriminations,

jellied secrets in fancy molds?

Forget the sermons. When Sunday comes,

let’s linger between sweat-glistened sheets –

you, me, our delirious savage heat.