Kyle Laws

After The Prose of the Trans-Siberian, Blaise Cendrars

“I forget where I am. I have to remember which direction,”

the woman in purple says as she descends circular stairs,

“traveling south or west as you pull from the station in Raton?”

The New Mexico landscape flattens into the desert off the pass,

into barbed wire that keep Black Angus and mustangs from

the tracks, the piñons that fruit every five years wide like arms

of a bear protecting her cubs, soil held to ground by short

grasses never plowed—the Dust Bowl never made it this far.We go south so we can go west, so we can stop at an early

Harvey House in Las Vegas, so we can walk the blocks

from Railroad Avenue to Charlie's Spic and Span Bakery

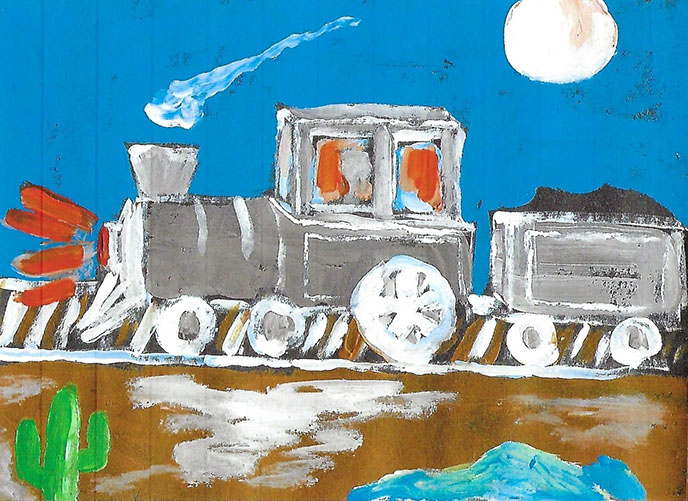

and Café, this not the Trans-Siberian, but crossing a country

as wide and deep, the locomotive growling at wild turkeys

climbing a butte across from a stone barn, a rusting Chevrolet

coupe beside, and bricks of adobe of a long gone ranch house

totems in the wind a red-tailed hawk glides over.

Leaving Raton Pass

We roll on rails into dusty green sagebrush and the yellow

of chamisa, into ground run by antelope and mule tail deer

and the meander of dried creek beds.No one had any hope of growing wheat here, or alfalfa,

in the flat stretches of baked grasses, a wide swatch

between the green-black of pine dotted hills.The occasional gold of cottonwoods still with leaves waves

along a running creek, highway a ribbon beside in the grey

turned soil of a volcano where tracks were laid.This is the path of the Santa Fe Trail, the Southwest Chief,

the interstate highway North/South, but before that the route

that led to the Camino Real to Mexico.The railway system was a new geometry beside dried stalks

of purple aster and black heads of sun flowers after the seeds

were picked by meadow larks and field mice made nests

in abandoned rail cars used to store hay.Eight black headed ducks paddle across what's left of the last

rain in a depression in the field. And a flock of starlings

descends into a one crossing town, goats behind houses

gnawing the ground close.When you travel by train you realize how open America is,

porous, how the water disappears as have people on the land,

more tractor trailers on the long haul,paths congregated like cattle, like Sunday under a steeple,

like stock tanks under windmills, dust swirls, devil of the plains,

kicking up along roads on All Saints Day for the folks passed on.

Quote from "The Prose of the Trans-Siberian…," Blaise Cendrars,

translated by Ron PadgettColorado’s Geometry

Where the roads are perfectly straight

and fields circular if irrigated by pivot,

but dry streambeds meander across plains

and lakes have the irregular hem of a skirt

made in a home economics class required of girls

that three years later becomes box pleated

in brown wool with tweed matched at seams.

Out of nowhere a canyon appearsyou can descend if the tread on your boots

is good enough, river that carved it called Purgatory.

Backed into the cliff is the outline of a house,

adobe gone back to earth, only the foundation left

and stubby poles that carry electricity from the top.

I cannot imagine what drives someone to these depths.

Kyle Laws is based out of the Arts Alliance Studios Community in Pueblo, CO. Her collections include This Town: Poems of Correspondence with Jared Smith (Liquid Light Press, 2017); So Bright to Blind (Five Oaks Press, 2015); Wildwood (Lummox Press, 2014); My Visions Are As Real As Your Movies, Joan of Arc Says to Rudolph Valentino (Dancing Girl Press, 2013); and George Sand’s Haiti (co-winner of Poetry West’s 2012 award). With six nominations for a Pushcart Prize, her poems and essays have appeared in magazines and anthologies in the U.S., U.K., and Canada. She is the editor and publisher of Casa de Cinco Hermanas Press. www.kylelaws.com