Charles Rammelkamp Review of

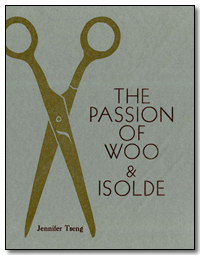

The Passion of Woo and Isolde

by Jennifer Tseng

The Passion of Woo and Isolde by Jennifer Tseng

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Fiction

Rose Metal Press, 2017

$12.00, 52 pages

ISBN: 978-1-941628-09-6

Winner of Rose Metal Press’s 2017 Short Short Chapbook Contest, Jennifer Tseng’s The Passion of Woo and Isolde makes me think of the old Taoist tale about Chuang Tzu falling asleep and dreaming he was a butterfly, only to wake up and wonder if he weren’t really a butterfly dreaming he was Chuang Tzu. In her stories, identities are as fluid as a yin-yang stew. In the opening story, “Past Lives,” a guard in an art museum strikes up an acquaintance with a female temp. worker whose job is to rewind tapes of the audio tour of an exhibit about angels. After several conversations, the guard confesses to the rewinder that he is sure he is her widow from a previous life. The rewinder apologizes, “feeling a pang of her old husbandly guilt.” But the guard waves away her apology, “and looked at her with the eyes of a very sad wife.”

In the penultimate story, “X and Y,” we learn that X emulates Y, a famous writer whom she takes as her role model. “She revered him. What they shared was the obsession with the appearance of humility, of being without drive.” But, Tseng writes, “A woman who models herself after a man is always tragic.” Yet their identities seem to slide around each other like eels.

In “The Locksmith,” the speaker (male? Female?) begins, “She was like no other woman I had ever loved.” In fact, her identity is almost indistinguishable from books, language. “She uttered paragraphs that sounded as if they had been meant for the printed page.” In her company, the narrator tells us, “I experienced the joy being alone in the company of another.” In the end, even the reader is incorporated into the fluid identity. “Like a book, she is readable and writeable. In this way I am never without her. As long as I have you, who also read and write.”

Truth, too, is fluid. As we already saw in “The Locksmith,” people are inseparable from language, speech. In the story, “Snow,” the narrator begins, “My husband will lie about anything at any time. Not big lies like, ‘I didn’t kill him!’ or ‘I swear I’m not having an affair!’” No, his lies are more along the lines of, “I’ll give you time. I’ll tell them. I’ll call. I’ll help you. I’ll cook. … I understand. I know what you mean. Everything’s fine. I’m fine. We’ll talk about it.” During a blizzard, in which they are snowbound, without heat, without food, her husband assures her, “The snow will melt by sundown.”

“Though I know the kind of man he is,” the narrator tells us, “for peace of mind, I believe him.”

The Passion of Woo and Isolde is made up of twenty-five stories divided into three parts, at the center of which are the stories of Woo and Isolde. Do they know each other? This

is deliciously, ambiguously unclear. Woo is an immigrant to the United States from China, married to a Caucasian woman. They have difficulty understanding each other (speaking the same language). This conceit is brilliantly captured in the story, “The Word Oh,” in which Woo is confused by his passive wife’s cries when they make love. There appear to be eight stories involving Woo (but don’t hold me to that count!), another three about Isolde that follow. Isolde has echoes of Heloise, of Abelard and Heloise fame, a pious but sensual character, curiously passive in the way Woo’s wife is passive, and her husband may have something of the opacity of Woo. When she has an argument with him, she decides that a particular black cat she encounters (the blackness of Woos hair is echoed here) contains “the spirit of her living husband.”

No, I’m pretty sure that Woo’s and Isolde’s passions are separate, that they are unacquainted, but just the fact that I can wonder about it shows the fluidity of identity and personality – of Reality with a capital R – that are evident throughout this provocative, alluring collection.

--Charles Rammelkamp