Books Received & Acknowledged

Matthew Borczon, Battle Lines, Epic Rights, www.epicrites.org, 49 pages, 2017, $10.

Matthew Borczon, A Clock of Human Bones, Yellow Chair Press, www.yellochairreview.com, (or see www.lulu.com), 42 pages, January 15, 2016, $10.

If Todd Moore were a middle-aged reservist with a wife, four kids, and was called for active duty in Afghanistan and when he came home with PTSD, these are the kind of poems he would write. These are long, skinny, short line, automatic weapon word bursts. This is a poet who doesn’t mince words or fool around as the first poems, in each collection, quoted in full below show.

Afghanistan 2010

Day 1

my first job

is to remove

156 staples

from the stump

of an Afghan

detainee

who swears in Pashtu

as my hands shake

and the marine

standing guard

laughs out loud

at his pain

and my fear.from A Clock of Human Bones

when I

got off

the plan

from Afghanistan

my youngest

daughter was

at the

end of

the runway

unsure of

who I

was.

from Battle Lines

If ever there was a need for effective, on the ground, retelling of war experiences, it is now. So many young people are being forced into the military because of a lack of job opportunities and because they are being force fed video game like misrepresentative garbage about what real war is all about. As the poet says as a subheading to Battle Lines, “poems: for some who serve the battles never end. “

Borczon is an important, relatively new voice, who should not be ignored. The only quibble I have with his work is some of those short liens lead to inevitable deadlines as “at the,

and the ... When I double checked my typing of the second poem quoted above I saw I had mentally corrected the line I objected to as.... at the end of. It is a small problem easily dealt with, if the poet chooses to. Todd must never have thought it was important as he never changed his style to reflect my objection. So, who am I to argue with the results?Alifair Skebe, Thin Matter, Foothills Publications, PO Box 68, Kanona, NY 14856, 78 pages, 2017, $16.

As always, Foothills goes the extra nine yards to produce a hand crafted, hand sewn book that is a joy to behold. Skebe is a poet of many dimensions whose work ranges from the stylistically esoteric. to more traditional blank verse. with a little of just about everything in between. There is much to admire here: work that amuses, delights, moves and reveals. I was particularly drawn to final piece, “To the Dead and Dying” which pays homage to Muriel Rukeyser, a poem of depth and discernment that feels particularly heart felt. Certainly more than the Emily Dickinson poem, “When I Died”, that plays like a kind of complex literary joke. If I have serious objections with this book it would be that the poet spends way too much energy with the formal aspects of the poems than with the content.

Bernadette Mayer, Work & Days, New Directions, ndbooks.com, 116 pages, 2016, $15.95.

The underlining structure of this wonderful book of poems is a diary of days and the work that fills them. Or so it would seems. When I say wonderful, I mean full of wonders. When I say seems, I mean that Bernadette means much more than what she seems. That is nothing is as simple as it seems. Bernadette’s days, mental meanderings, complex reference points, are a compendium of a truly remarkable sensibility that is both far ranging and totally rooted to where she is now. Or so it seems. No one day is like any other day in Mayer’s world. And this is why her books are a reading experience unlike any other.

Howard Kogan, A Chill in the Air, Square Circle Press, www.Square CirclePress.com, 86 pages, 2016, $12.95.

One of the blurbs on the back of Kogan’s book is by Bernadette Mayer and says in full, “I want Howard Kogan to write things that make no sense. Read this book and see why he won’t.” It would be difficult to find a poet more unlike Mayer than Kogan, though he has been studying with her for some time. Howard’s poem are filled with the stuff of life, sadness, the perils of aging, family history, often fraught histories, due to the Diaspora of the Jews in Germany and the inevitable loss; all of it, though told with a wry, knowing hand and eye. Kogan handles the most difficult personal subjects with a deft choice of words, that belies a sense of despair by implying that: if you didn’t laugh, you’d have to cry. Only a true artist could manage this difficult dichotomy of subject and tone with such delicacy.

Wayne F. Burke, Knuckle Sandwiches, Bare Back Press, www.barebackpress.com, 100 pages, 2016, $14.95.

When you have an in-your-face, literally, title like Knuckle Sandwiches, and a very serious looking older man shaking his fist at you from the back cover, you expect a certain kind of confrontational style. And you will not be disappointed. There is more than a little Todd Moore here, lean, staccato hard-hitting lines. Some Michael Casey in his Vietnam days as the “doofus,” a man who mixes it up (Casey was an MP in Nam) with the big boys. Burke has a keen, no bullshit eye and style that gets the job done, then gets bails. Like a first round TKO. Throw in some Bukowski: a gruff, womanizing, hard drinking exterior that camouflages his “sensitive” side as a reader, a listener to classical music and even moments of sentimentality, albeit brief, and you get a fuller of picture of Burke.

I hesitate to evoke the poetic God of meat/ bar poetry like Bukowski (one Bukwoski was more than enough, perhaps too much and his legions of imitators have not yet grasped that fact and may never do so.) as Burke is no imitator, but a genuine hardass when he wants to be and has a clear, immediate voice of his own.Sat on a bench in sunshine

and the whole human race

went by me

in trucks and cars and

on foot and

I did not give a

fuck about any of it

except the sun

on my face,from “Reality”

Reading Knuckle Sandwiches, I recalled a former institution, a bar on the main drag in Troy, N.Y called Burke’s where working class people and the hard line local boozers gathered for cheap beer and monster sandwiches to drink, eat and solve the world’s problems. It was affectionately known as Burkie’s, a name Wayne professes to hate, so you know it was not his place but you sure could imagine him hanging out there. Of course, it closed when old man Burke got too old to run the gin mill and it was replaced by nothing.Dan Wilcox, Inauguration Raga, A.P.D. 280 South Main Ave, Albany, N.Y. 12208 apdbooks@earthlink.net, $4 postpaid, roughly 18 pages.

This long poem in the manner of Ed Sanders investigative poetry essay is a kind of experiment in terror. Not so much as the content but how the poet receives it. Wilcox had two TV stations broadcasting the Trump inauguration and immediate aftermath, taking notes, and transcribing them into a Ginsberg style homespun American raga. We have the immediacy of the event itself, superimpositions and flashbacks of past inaugurations such as the Nixon one, the president Trump is destined to be compared with, and oaths of office: the poet’s upon is induction into the armed services and The Trump’s oath accepting the reins of government. The fact that Trump skipped the induction into the services due to some bogus health issue (bone spurs in his heel and was quoted as saying his Vietnam was having sex during the STD era of the 80’s!?) seems significant as he ass kisses the generals now in a vain attempt to appear as a legitimate tough guy. There is a distinct difference between battle hardened tough and a loud mouth bully tough, something Trump is destined to learn the hard way. But I digress and the poet’s digressions in this long poem are far more poignant and relevant than mine. Contact Dan at the above address and be part of the poet’s history of America. As Sanders astutely observed every generation writes its own history. There is no reason why the poets of our generation can’t write that history for our generation.

Black cars & lines of guards in black

Marine action-figures by the steps

Obama’s approval rating now

Higher than Trumps

Helicopter rises from the Capitol

3 consecutive 2-term Presidents

The way the Founding Fathers

Mean it to be

The way the Constitution says

It should be(Of note APD, Dan’s Press, stands for, in this case, a presidential disaster. What the initials stand for our subject to change due to current events whatever they may be.)

Joan Colby, The Seven Heavenly Virtues, Kelsay Books, Aldritch Press,www.kelsaybooks.com.,

96 pages, 2017, $17.Anyone who follows Joan Colby’s poetic output knows no one can take a subject and run with it the way she does. Her previous book was a far-ranging examination of all aspects of the circus while this one examine as a different kind of pageant, Christian Religion. This is a very catholic book and I mean that first and foremost in the original sense of the world, as in embracing a wide variety of things, though there is no doubt that the book is rooted in the Catholic faith. After twenty-five years working in an Irish Catholic environment, I can assure you: “There is no such thing as a lapsed Catholic, just varying degrees of guilt.” Colby goes beyond the belief to examine the nature and history of belief in The Seven Heavenly Virtues.

Among her topics are the blending of sacred and profane love, pagan and Christian mysticism, the blending of the temporal and the corporeal. There are always two ways of looking and seeing in these poems, the here and now and the beyond rooted in faith; we can question but can we ever be sure, no matter how profound our belief? There are no simple answers here, nor should there be. Where is God in the terrible poetry of war? Does a sincere and deep Faith become exclusive when it denies another way? And what of these other forms of belief? The world is, as she asserts, a terrifying cathedral.

This formidable, excellent collection closes with a poetic response to the number: The 7 Deadly Sins, the 7 Heavenly Virtues and the 10 Commandments. There is doubt and affirmation here, a book that poses eternal questions but often answers them, or, rather, provides direction in the here and now. What is sure, this is a book of believers and non-believers alike.from “Writing the Wills”

A pause-do we have nursing home

insurance? I think of my friend

Who when asked, said,

“A shot gun and a bottle of whiskey.”Brief Reviews

Two from Dancing Girl Press:

Cathy Porter, Exit Songs, dancing girl press, dancinggirl.com, 25 pages, $7, 2016.

Kathleen Kirk, Interior Sculpture, 27 pages, $7, 2014.Dancing Girl is a new, one woman press, which has its good points and bad points. The good is the time and attention spent designing and executing individual, high quality books. The bad is that she runs way behind time (understandably) and is slow to deliver orders. All things considered it is worth the wait for reasonably priced, excellent chapbooks of poetry.

Porter’s poems are signature, final moments in the lives of a variety of doomed rock icons ranging from Elvis to Buddy Holly to Michael Jackson to Hank Williams and everything in between. All of these brief elegiac poems create a sense of the people and the tragic endings of lives shortened by misadventure. The popular music industry seems to attract highly gifted performers and artists with a hell bent to destruction way of life. Maybe that contributes to what makes them so special that years, even decades after their deaths, we still listen to their music. It should be noted that knowing the work of the performers in question heightens an understanding of the poems but isn’t necessary as they stand on their own as odes to destruction.Dad knew- fragile systems

do not last long in a world of show-me now.

What did you see when the lights went out?

Was that last swallow worth wherever you

are now? You’ll never get to rehab this way,

no, no. no....from “Amy”, the concluding poem in Exit Songs

Kirk’s collection is a series of voice poems about the life and times of Camille Claudel.

Claudel was the lover, model and inspiration for the much more well-known sculptor Rodin but was also a respected, even renowned sculptor herself who, tragically, spent the last decades of her life confined to an institution following a breakdown after their relationship ended. Whether she deserved to be confined, was actually as mentally distressed as was claimed, is an open question. One thing for sure, after her confinement, in the prime of her life, she never worked again. Much like the “Broken Figure” in the poem of the same title, Claudel’s dream, life and creations turned to dust. Kirk captures her despair, the tragedy of her life in brief, telling moments of personal reflection as only a true artist could.Two from Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, PO Box 12375, Milwaukee WI, 53212 (vegetarianalcoholicpress.com):

Heidi Koos & Nathan Fredrick, Parallelograms, 56 pages, no price listed, 2014.

Troy Schoultz, Biographies of Runaway Dogs, 55 pages, no price listed, 2016.What to say about Parallelograms? Two distinctly different poets, in two different colored ink, take on the same subject with wildly idiosyncratic results. Subjects range from Secret deals, to Lingerie, to Windows to Allen Bradley with others apparently chosen at random. I guess the question should be, does it work? Well, if you are looking for a cohesive, collaborative voice, where one person picks up from the other and goes with it, no. If you want two controlled crazy voices seemingly riffing on something to their heart’s desire, wherever the riff takes them as a kind of jazz improve with words, well, then Yes, yes it does. In spades. It would be senseless to quote anything as any selection would be totally out of context and do no one justice. I thoroughly enjoyed these guys playing around in the language with whatever came to mind at the time. (I don’t mean to suggest these were not edited or feel made-up on the spot as this too would be an injustice and not at all true.) I couldn’t resist and author who says, he studied English at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee where he learned everything needed to become a great bartender. I know the feeling. This collection show that wasn’t all he learned or Koos either, in her time at Marlboro College.

Schoultz’s collection is much more rooted to specific times and places that the previous offering from the press. These pieces are all of the narrative type, have the feeling of autobiography, and feel earned, during a lifetime of disappointed dreams and thwarted aspirations. Jobs are menial, skills are wasted, and love is a forlorn hope. Drinking in bars gets you nowhere but still you go on because well, what else can you do? This is life in the slow lane, where most of us life, here, now and everywhere. Schoultz makes has no pretentions, just an honest look at keeping on with keeping on. If you want elevated language and profound thoughts don’t read this book. If you want the real nitty gritty you should read Biographies of Runaway Dogs.From Rattle,ww.rattle.com, all $6. postage included, all runners up to first national chapbook competition:

April Salzano, Turn Left Before Morning, 39 pages.

Heather Bell, Kill the Dogs, 34 pages.

Denise Miller, Ligatures, 35 pages.It would be difficult to imagine three more different women than these runners up in this first, very promising, chapbook competition. Throw in the winner and you have an excellent cross section of concerns, attitudes, and politics of some of the more meaningful issues confronting us today. The winner focused on survival during wartime and immigration as a necessary escape from a hostile, life threatening situation. Miller touches on some of the same issues only it living as a black person in a hostile white world that is the life-threatening problem. Using news articles of black men and women killed by white people, usually officers of the law, her fear of what the future offers for black people is as terrifying as it is real. Salzano’s poetry is more blood line personal, dealing with the care of her autistic son, a care giving situation fraught with love and hopelessness, knowing it never ends. But oh, how she loves her boy. Bell seems to be more down to earth and less issue focused but still there is a sense of imminent danger in everyday life. She is a parent, a wife, and the woman with the blue hair who has been known to smoke a joint and indulge in casual sex and alcohol abuse, but despite all this, she is as rooted as the other poets in a place and time that does not favor women as people. She is an outsider in Trumplandia where women tend to be blonde not blue. All of these women offer poems that will break your heart. Bell can make you smile, Miller makes you stop and think and ask questions and Salzano makes you want to say a prayer for her and her loved ones, even if you don’t believe in a merciful god.

A brief aside. When I was working in the tavern, about fifteen years ago, I tried to explain to Moron, the not so affectionate nickname for the resident bar drunk, some basic realities about modern life. Of course, I knew he wouldn’t listen, as Moron was a man who had an opinion about everything but no facts to back any of them up. I said it was time to make room in his life for the idea that the women in the convenience store he didn’t like to go to anymore for his cigarettes, had green hair, and she was the only one who knew what she was doing. You might not like it but facts were facts, she may look strange to you, she might even have body art and a piercing or two, but when it came right down to it, she knew her job and she did it well. He would not be convinced.

He was the kind of guy whose response to his personal physician telling him his blood pressure was out of sight and he had to stop drinking and smoking, was to drink more and smoke between two and three packs a day. His response to well-meaning advice from people, such as myself, who had problems with alcohol, was to pace himself while he as in the bar, but drink twice as much at home.

I overheard him, not long before he was barred for life, telling one of the customers in a drunken screed at a quarter to twelve in the morning (just before I cut him off at one beer) that his Doctor had given him a final warning, stop drinking And smoking or else he wouldn’t be responsible for what happened next.

Last I heard, Moron had learned how to kind of walk again, after a series of debilitating strokes after going cold turkey, unsupervised, against doctor’s advice. I thought of my grandmother who liked to quote truisms to live by, which I generally ignored, but one always made sense to me: ignorance it is its own reward. Sometimes you just have to listen and except the fact that not everyone is blonde and a wasp and hot as hell. That women’s sports can be fun to watch even if they do sweat when they are competing. That drooling, slobbering, loud mouthed rednecks don’t generally make exciting bedmates. And so on and so forth. I often wonder what happened to the girl with the green hair. She was nice.T.K. Splake, Ghost Light, splakes@chartermi.net, no price listed, 44 pages.

The indefatigable Mr. Thomas Smith aka T. Kilgore Splake has released another reflective collection addressing the eternal question of Death. The title directly refers to the practice of each theater always leaving one light on, the so-called ghost light, as

every theater is said to be haunted. The front and back covers have eerie color photos of a ghost light that set the tone of the poetry inside. In a well-produced, slick staple bound collection, typical of Splake’s self-published books, the reader faces the inevitable cessation of life, a very real concern for Splake now entering his 80’s, with clear eyes wide open. He takes us through an imagined death and the fleeting images of past life and his recurrent theme of his emergence of his second, “real life”, as a poet. This reader remains impressed by the poet’s quest for truth as Splake enters a cave to seek residues of spiritual knowledge the cave may contain. Not exactly a walk in the woods for a reminiscing old man at the end of his life as depicted in a Splake favorite, Bergman’s Wild Strawberries, but a risky adventure into the unknown. His brief video where he reads in the dark inside that cave bear testimony to his relentless quest for truth. Long may he live and thrive.

Michael Estabrook poems, drawings Wayne Hogan, Two Sides of the Same Coin, little books press, po box 842, Cookeville, TN, 38503 no price or page count, roughly 60 lavishly illustrated pages in a slick format.

This collection, as the title indicated, is a joining of congruent minds. Estabrook’s poems are a combination of fears (phobias) and obsessions (philias) ie. Neophobia (fear of new things) versus Sophophilia Love of Learning. Most of the poems are light hearted and witty, as they explore the deeper aspects of the mind. All are told in progressive, linked five line stanzas. The poet writes that he hopes the reader will find it (the work) enlightening, amusing, interesting, distracting , irritating...anything but boring. The author needn’t fear, as there is much to enchant in this clever, beguiling book.

As a self-confessed Waynephiliac, as in Wayne Hogan fan, I was enthralled by these drawings, quirky as always, but with a slightly dark, edgy quality to them (not that Hogan is Ever really dark: grotesque maybe, satirical but dark, no). The paring of the poet’s work and the artist’s unique talents, is as perfect as such a collaboration can be. From the faceless, polka dot infused faceless women on the front cover, to the female Marat on the back one, the self-effacing Wayne Hogan pens one hit after another.

Martin Raninqueo, linocuts by Julieta Warman, translated by John Oliver Simon, War Haikus, Red Dragonfly Press, www.reddragonflypress.org, $10, 41 pages (poems in the original Spanish with English translations), 2016

This brief, but exquisite collection, is a rare deviation of the form where war imagery becomes the force of nature that is the main attribute of the poems. Far from being intrusive, the gruesome imagery intermixed with natural conditions often results in poignant images. The poet speaks from personal experience as an unwilling conscript into the Argentine armed forces to fight the British in the Falkland’s War. He witnesses extreme fighting, is captured and held prisoner, experiences that all have a significant place sin these poems. Anyone interested in how flexible the haiku from can be, must see this collection. The linocuts are equally as impressive, dark images in a field of blood rampant.

Sun hits the mountain

we sing the National Anthem

(feigning courage)Don Wentworth, With a Deepening Presence, Six Gallery Press, ISBN 978-1-926616-86-5, available from Amazon.com, $10, 98 pages, 2016.

Wentworth, long time editor of Lilliput Review a magazine dedicated to publishing small poems in a small format, is a master of the haiku form. His poems are imagistic, spiritual, funny, have all the necessary components of great formal poetry. One poem, chosen at random, illustrates just how much of master craftsman Wentworth is:

lightning flash

how brief

the seeing

Contact the poet for this reasonable excellent collection. If you love the short haiku styled poem, you will love this collection.

Gillian Cummings, My Dim Aviary, Black Lawrence Press, www.blacklawrencepress.com, 53 pages, $15.95, 2016.

Cummings has the rare gift and ability to inhabit a semi-mythical character in this excellent series of prose poems. The subject is a French model/prostitute who was the subject of a series of “post card” photos that were sold on the black market in the early 1900’s. Although little is known of her life, this is actually a plus for the poet who gets to live inside her head and create a believable, visceral sense of place and self. While the life verges on the sordid, there is humor and pathos, joy and despair in almost equal measures as she ages and her beauty begins to fade. Time dissolves the images and the life but what Cummings has created is an indelible portrait of a “fallen angel’s” reality.Scott Wannberg: The Lummox Years 1996-2006, Lummox Press, www.lummoxpress.com, 165 pages, $20, 2016.

This hefty volume includes, a generous miscellany of poems, reviews by the poet, brief essays, tributes by friends and fellow poets and two complete chapbooks that editor Armstrong published in his Little Red Book series. By all accounts, Wannberg was a semi-legendary figure in the West Coast poetry scene as a reader, raconteur and personality. It is easy to see why as you delve further into his work. After all three of his large books attracted the attention of a small press owned and operated by Viggo Mortensen (yes that Viggo Mortensen...could there be another one?) While, I was a regular contributor to Lummox back in the day and had seen most of these poems previously, they feel fresh and new in this ample collection. If Wannberg has a fault, and we all do, it is that many of his poems feel flat on the page, discursive and clearly would be better appreciated spoken aloud. That said, by the time you get to the second Little Red Book, his affinity for jazz, the Beat rhythms of his poems are electric and magical erasing initial impressions to the contrary. R.D. should be complimented for keeping this poetic spirit alive, of resurrecting his voice much as Kurt Nimmo did for Steve Richmond.

Tim Dardis, Road Rash, Toad Suck (Shakespeare & Company), no other information listed, 70 pages, $10, 2015.

Dardis seems like a regular guy: he loves the outdoors, fishes, rides his mountain bike, hikes. Is a bit melancholic: pines for women he won’t date, in fact, seems to be unlucky in relationship with women but he is not depressive or excessive in his emotions. He can be exuberant, mostly when outdoors, but can be reflective. His best poems are simple but not simplistic, taking an everyday activity such as massage and transforming into something special,

You test my range of motion

I like my honest answerAt our next session you declare

You’ve met someone, haven’t you!Yes, I reply, eagerly

waiting for you

to dig into my wound

(from Soft Tissue Work)

Two of the concluding poems touch on alcohol abuse and recovery. In the first, “Alcohol Recovery Center” they say the Serenity Prayer at the end of the session and is thankful he doesn’t need to be a client here. Later, he quotes a man in Recovery in his poem “Sober”I don’t

want to kill myselfThat’s what the guy said

I wake up

and get to hear the birds sing

Robert Cooperman, City Hat Frame Factory, Kelsay Books, Aldrich Press, kelsaybooks.com, 115 pages, 2017, $17.

You don’t have to know the author to immediately recognize that this is a labor of love. Cooperman details days of his youth working at his dad’s factory in the lower east side, presenting a vivid portrait of the people who work there, himself as naïve, inexperienced 15-year-old, and most of all, his parents. His father was movie star handsome, a golden gloves fighter, and a man beset by financial worries, not the least of which, was a randy, chiseling partner. The senior Cooperman tries to keep the business going knowing he was working in a dying industry where hats were no longer a staple of everyday wear. What Cooperman does best, in this excellent series of linked poems, is present a clear picture of what life was like on the floor of the factory. Along the way we see the poet growing as man slowly realizing the twenty minute breaks which his delivery partner made were more than consultations with a client, that his father, despite having to pay less than decent wages to his workers in order to keep the enterprise going, was more than decent man, but someone who deserved love and admiration. Desperate times, desperate measures. There isn’t a page on this book that does not reflect a deep caring and present a loving portrait of his family.Guinotte Wise, Scattered Cranes, Pski’s Porch Publishing pskisporch@gmail.com, 134 pages, 2017, $10.99.

Wise is an amiable companion with a country twang. He has held innumerable physical labor jobs that lends experience to a keen eye for people and places mostly through the South and Midwest before alighting in Kansas. The poems I enjoyed the most had a kind of headlong momentum that were a cross between a Jack London blizzard story after four pits of brandy and a couple of six packs of PBR and Cheever’s The Swimmer after three extra dry martinis. You can almost hear the bluegrass band tuning up in the background as he sets pen to paper or approaches a microphone to read and that is a fine thing. You can hear the droning of air horns, experience an evening at drive in theater that was always so much more than some popcorn and a movie. Feel the road rush of coming down after a long haul at a breakfast for Denny’s. The observation that there’s another Denny’s, must be time to eat, is not a casual or flippant one.

On a more serious note, one should not ignore the cover illustration” origami cranes on a puddle of blood. Sand hill cranes. and the abuse of their habitat, of the birds themselves, are a recurring motif in this collection. As I read the terrific poem, “Sand Hill Cranes” I was reminded of the first time I saw one of my namesakes, (George Catlin) shooting the flamingo’s painting. The piece was one of several commissioned by Colt, the gun manufacturer to demonstrate the efficacy of their new repeating rifle, in action. The artist lovingly describes the beauty of the birds, their sleek lines and colorful combination of pinks and how graceful they are in the wild and then massacres, what appears to be hundreds of these birds with the new Colt creation. It is truly one of the most ghastly paintings ever commissioned and may just be the first instance of product placement in history. The same sickening feeling emanates from Wise’s excellent poem of the callous disregard for avian life and their habitat. It should be noted that the Keystone Pipeline was slated to cross this delicate area and no doubt ravage the landscape and inflict irreparable harm on the species.John Guzlowski, Echoes of Tattered Tongues: Memory Unfolded, Aquila Polonica, www. AquilaPolonica.com, hb, 171 pages, 2016, $21.95.

How does one quantify pain? You can’t really. Which is why reviewing a book such as Echoes of Tattered Tongues is, essentially, an impossible task. What I can say is Guzlowski relates the history of his parents as slave laborers in Nazi German camps. The poems are unflinching, honest and brutal often all at once. The stories Guzlowski eventually ferrets out of his reticent mother’s memory, after his father died and she was dying are almost unimaginable in their cruelty. At one point, near the end, the poet, insists that she not tell him anymore about the brutalities inflicted upon young women that she witnessed. Enough is enough, he thinks. He knows as much as anyone needs to know as do we by the end of this heroic achievement. And there is no other word for this book but heroic. What was his parents’ crime? They were guilty of being Polish. Not even Jewish, they were Catholics, just Polish.

Photos of Dead MothersThey are simple as arithmetic. One minus one

is nothing. You see this in their blind, dumb eyes,

the twist of their bodies lying in the mud,

the truth of their silence. There is nothing

to tell one mother from another. They are dead.No one has anything to grieve or remember.

The mouth cracked open tells you nothing

about her first child, or that day in the church

that meant so much, or the happy time she stood

before the Christmas tree knowing how much

her daughter would love the light blue pitcher

she gave her, no matter how little it cost.

(poem quoted in full chosen at random)t. kilgore splake, Last Dance, transcendent zero press, wwwtranscendentzeropress.com, 45pages, $9.98, 2017.

Splake continues his poetic journey through life with another Beat driven chapbook. Not content upon choosing one of the Frost paths, he travels for some 40 or so years down one, decides that particular path is the wrong one, backtracks, and chooses the other path instead, reinventing the conventional Tom Smith of Path 1 into the Path 2 poet, t. kilgore splake. As has been his way of late this collection is mixture of short, hard hitting poems and longer more narrative ones. I continue to be drawn more to the shorter ones three of which I will quote in full below.

opening day

monofilament whisper

reaching for heaven

writer’s blockwaiting appearance

of magical words

like new tattoo ink

burning into fleshthirteenth step

steep long night hours

many afternoon naps

dreams of icy beer

hot flash rush

johnny walker blackAyaz Daryl Nielsen, Window Left Open, Prolific Press, from the author, darylaz@gmail.com, 36 pages, $8.95, 2017.

Nielsen is a master of the haiku form. In this brief but wide-ranging collection he shows off his well respected abilities:an owl’s aria through

the sleeping aspen

mouse, the late-night martyr

in the maple above

this flat tire

crow being crowEach poem is a vivid slice of pie of life: some humorous, some indecorous, some wryly amusing or poignant moments in time; all of them effective.

Editor, Teresa Mei Chuc, Nuclear Impact: Broken Atoms in Our Hands, order from Amazon or Barnes and Nobel, 556 pages, 2017, $25.

I have always felt it was unethical and unfair to review a book that I had not finished but I will make an exception for this anthology. This is a massive tome, a substantial undertaking so vast it might take years to finish. While I have a pdf copy, I can easily see this as a desk top or coffee table book, for the serious readers of topical poetry. There is nothing more topical that nuclear waste. In the less than a century since the harnessing of the atom there has been no adequate, even barely adequate, solution for how to handle radioactive material. And yet we persist in the fantasy that atomic energy is a viable option for future use as power generation. The only thing certain about is it is toxic, the effects are long lasting, as in centuries, not years but many centuries, maybe even eons, although one eon is more than enough. The poems in this anthology, that I have read, are all sincere, thoughtful, often personal narratives of what the nuclear age means to us. Drop a bomb on a city, while it may not impact us immediately, the possibility exists It could happen here. This is not an idle threat given the current state of world leadership and unstable guardians of a nuclear arsenal. The others’ guys are even worse. Buy this book, read it, ignore what over 150 chosen poets have to say at your own peril.

I’d like to offer a poetic gesture of my own that I think reflects the spirit of the book., If you like this piece, you will like what you see inside Nuclear Impact,Pastoral with Nuclear Sunset

Prevailing winds create waves

in the uncut fields, white

tips of grass gone to seed

near dusk; the multi-textured

sky, pied beauty, a dappled thing,

burnt orange on blue turning red

where the night should be.Kyle Laws & Jared Smith, This Town : Poems of Correspondence, www.liquidlightpress, 33 pages, no price listed, 2017.

My blurb for this fine collection is quoted below:

As expected when two excellent poets, in this case, Kyle Laws and

Jared Smith, combine efforts to create a poetic dialogue, the result is

something special. The poetic landscape they create is, at once, as palpable

and as immediate, as the memory of every place you’ve ever lived, and a

unique geography of the imagination with real people in it. Go to town.

Experience all that life has to offer.

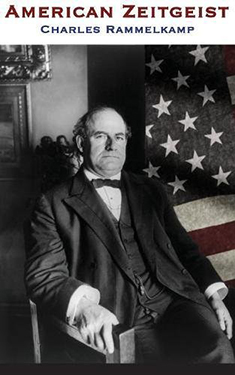

Charles Rammelkamp, American Zeitgeist, Apprentice House Press, www.apprenticehouse.com, $12, 146 pages, 2017.

My blurb for a terrific collection of a book based on our history. We need more history and poetry in our everyday lives:

American Zeitgeist is a narrative in verse of a historical footnote, statesman William Jennings Bryan. Bryan was a Populist Democrat, a true man of the people, who remains the only candidate to run for, and lose, three times, the election for president of the United States. Despite planting the seeds for Progressive policies, as a man who honored the spirit and tenor of American Democracy, Bryan is mostly remembered for being on the wrong side of history. As a man of deep religious conviction and a dynamic public orator, his defense of Creationism in the infamous Scope Trial, marked him forever as a reactionary crank. Rammelkamp gives us a much larger context to consider the man's life and work. May our best poets continue to write our history.Received, Acknowledged and Recommended

Jon Wesick, Words of Power, Dances of Power, Garden Oak Press, gardenoakpress.com, no price listed 120 pages, 2015. Political poems often with a humorous/ironic twist. Not to be missed “Foul, if Allen Ginsberg had written greeting cards” and “Cesare Borgia in Heaven: and Postmodern Epistemology.”

Kathleen McCoy, More Words Than Water, Finishing Line Press, www.finishinglinepress.com,

$13.99, 36 pages, 2017. Heartfelt, well expressed elegiac poetry.Ruth Moon Kempher, In Magikal Waters, Finishing Line Press, www.finishinglinepress.com, $14.99 31 pages, 2017.

Kate McNairy, Light to Light, Finishing Line Press, www.finishinglinepress.com, $14.99, 26 pages, 2016.

Ed. Dianne Borsenik, Delirious: A Poetic Celebration of Prince, nightbaletterpress.com, $10.00,

92 pages, 2016.Laurel Speer, Trying to Make Sense Out of That Jar, poetry pamphlet, from the author @ PO Box 12220, Tucson, Az, 85732, 20 pages, 2016, $4.

Ed. Dave Roskos, Big Hammer (annual anthology), PO Box 906, Island Heights, NJ 08732-0906. Substantial, big assed book of poetry and art.

Susan Edwards Richmond, Before We Were Birds, Adastra Press, 16 Reservation Road, Easthampton, MA 01027,77 pages, 2017, $18.

Prose Reviews

Rosalind Palermo Stevenson, The Absent, Rain Mountain Press, www.rainmountainpress.com,

327 pages, $18.00, 2016.As in the Dylan song, “A Simple Twist of Fate”, Stevenson’s book came to me in conjunction with the novel, Fever Dream by Samantha Schweblin. I read that exquisite book concurrently with The Absent. The former is the last moments of strange relationship between a young man and an older woman on her death bed. If there are facts to be gleaned from their relationship, they exist in the mind of the reader, as the dialogue the two share becomes more and more intertwined with fevers and dreams as it progresses. There is no palpable reality. The same could be said between the deepest relationship in The Absent. The protagonist is totally devoted to his first wife, who dies from complications of a miscarriage early in their marriage. Despite her having passed on she dominates everything that he is, and all that he does, for the rest of his life even during his second, successful marriage. What is absent is clearly the thing that is most present.

Lucie, the dead wife, was a photographer’s assistant in the nascent days of photography. She learned her skills working with the husband, a professional photographer, and begins taking her own pictures. Images in her photographs continue to beguile long after her death. Always there is something ineffable that inhabits her work, that is not clear to the eye, may not even exist in the physical sense, but whatever is there in spirit dominates her compositions. This is the metaphor, the essentially conceit of the novel.

What is most extraordinary about this book, and there are many extraordinary aspects of it, is the language. I can think of maybe three novels that one can definitively say are extended epic poems: Kate Braverman’s, The Incantation of Frida K, and Toni Morrison’s two novels Song of Solomon and Jazz. Now, there’s a fourth, The Absent.

The language is incandescent, luminous, illuminating in a way that is beyond compelling. The book is almost hypnotic in it sheer ability to captivate the reader, pulling him forward into this world of clarity even when he is lost in shadows. There are plots here, quite well-researched, fascinating ones, but it is the flowing and flexing of the words that fascinate me. Later, another photographer’s assistant plays a pivotal role in the novel, one who is blinded when a developing solution blackens her eyes. Something she had seen in a photograph of an Indian, perhaps the essence of his soul stolen by the photograph, causes her to lose her equilibrium, an act of carelessness or fright? Whichever it is, the result is permanent and devastating. An essential irony is that even blind, the images from the photographs continue to haunt her. She is blind but she is defined by what she “sees.”

My original notes for this book are shards of colored glass, fragments of a kaleidoscopic vision that feel continuous even as the words and images pull apart. They are pieces of poetic puzzle, more image than specific notations. I had the clear sense, by the end of the novel, of being on a death bed, in a fever dream, in which the whole of a man’s life is unraveling on one long, accelerating reel of images, of a “my whole life flashed before me” end of life experience in Technicolor. The absent are present even when the principles are physically far apart. Like Stevenson’s previous work from Rain Mountain, Insect Dreams, the reader’s perceptions are most lucid when they are enmeshed in dreams. If the dream is reality, take me to that world and leave me there. Everything else, before those dreams and after, not of these vibrant living, breathing places, is merely the mundane facts of everyday life. This book is timeless, so remarkable, describing it pales beside the experience of reading it.

Nava Renek, Where the Survivors Are Buried, Rain Mountain Press, www.reainmountain press.com, 250 pages, $18-, 2017

Where the Survivors Are Buried is an apt title for these two, skillfully written, complimentary novellas. The first, Walking East, focuses on a woman, Meem (diminutive of Miriam) who is on the cusp of middle age and not handling it well. She is no longer the young, fearless, free spirited, self-indulgent wild child but a woman fifteen years into a safe, but no longer thrilling, marriage to Grant that has produced a precocious, but needy son, Oscar. Meem claims to love Grant, and in her feckless way, she does. She clearly adores her son but still the allure of another man, Jeff, strains her commitment to her married life. Miriam feels the need to be involved in the rock scene she once fancied herself a member of. Jeff provides the means and the opportunity. The pull proves irresistible.

It is obvious to everyone that Jeff is only interested in her as a nice, still attractive, piece on the side. He has no emotional attachment to her nor would he. Still, Meem invests her unrealistic dreams of the life that never was, and still might be, in a pipe dream. That Jeff is also very married should be a major red flag but even as Meem sees it waving, she ignores the warning signs.

Jeff is a shallow, transparent, facile opportunist in all ways, especially where Meem is concerned. Certainly, she is not the first women he has used this way nor will she be the last one. At some level, Miriam senses this, but still refuses to admit it to herself. Jeff remains a representation, an embodiment of the youth she no longer has: the excitement, the drugs, sex, and rock ‘n roll of her youth. None of this not going to end well.

Her husband finally persuades Meem to see an analyst in a desperate attempt to save their marriage. Grant may be predictable and boring, but he is kind and loving husband. They both know Oscar needs his mother, whom she has been a stay-at-home mom for the first eight years of his life. The last thing Meem wishes to do is hurt her child but all she hears are the sirens calling.

On a trip west with Jeff for the rock magazine she writes for, Meem interviews and anorexic diva who is clearly so far past burned out you can smell the ashes inside her about to spew forth. Still, on stage, the diva can electrify. Her charisma is undeniable, under the right set of lights. The magic and energy the crowd and the singer share is elevating like a form of emotional crack. Once the high is over though there is nothing but the shell left behind. Miriam sees only the magic but resists the emptiness after the magic acts; it is all a trick, a momentary card pulled from a sleeve.Upon the return from her trip, Miriam continues to pull away from her safe place. She rejects the analysis she feels is counterproductive even as it reveals inescapable emotional truths. There is no happy ending here. This is what life is like, is what people do, despite the obvious self-defeating nature of the choices they are presented with.

The second novella, Fly Away Home, is told from the point of view of a therapist, Elliott, who offers practical advice and insights into other people’s lives but refuses to see the same issues in his own relationship. He imagines himself as a kind of cocksman, might even have been one at some point in his life, but like most self-styled God’s gift to women, is so self-assured, he believes he can do no wrong. He is the worst kind of self-deluded narcissist, the kind who has a reverse Midas touch for interpersonal relationships. Not exactly a strong job recommendation but there it is. Consequently he, makes the inevitable unwise choices that feed his ego at the cost of end of deeper connections; his marriage.

Much of the narrative involves a vacation on the Jersey shore with his two daughters. The trip is a concession by the ex-wife to allow the children an extended, unsupervised time with their father but only within the strictures of a x- amount of miles-from-home limitation. The shore has some attractions for the children but they aren’t the tony Maine vacations or the Cape Cod locations he prefers. Never shy about pampering himself and indulging his fantasies, even in his dreams and reminiscences, Elliott remains a prisoner of his immaturity. His arrested development seems to have stopped somewhere in his early teens and seems destined to remain there for the rest of his life. When he meets an attractive, potentially available waitress, their meeting seems destined to lead nowhere, as much because of the nature of their lack of proximity, as it is his inability to clearly empathize with her need for a meaningful relationship. Just as well for her there are no firm plans for them to meet again.

Elliott is the male version of Meem in many ways: 40ish, ruing lost youth, facilitating a broken relationship with much more clear thinking, much more mature partners, with a resultant loss of self-esteem in that brokenness.

Is Elliott the stern voice, the therapist of the first novella who constantly leaves sessions to take calls from someone? He could be, as the last name only is used in the first novella while the first name is used in the second book but not the last.

And are those calls that so disrupt Miriam’s session from the borderline psychotic, beautiful actress who seduces, threatens, and ultimately ruins Elliot’s professional and personal life? Maybe. As with Meem, the reader can see what the character cannot. Elliott is living in a fantasy life that is embodied in the search through the town he grew up in for a crystal palace ice cream Xanadu with his children on the way home from the Shore. It no longer exists. Or maybe never did, certainly not in the way he recalls it. Life will go on for Elliot but the implications are clear: a middle age adolescent will never achieve any kind of meaningful self-understanding. Both of these novellas are finally polished gems told in a believable, convincing way.Stephanie Dickinson, Girl Behind the Door, Rain Mountain Press, www.rainmountainpress.com, 238 pages 2017, $15,

“Navel gazing is not for the faint of heart. The risk of honest

self-appraisal requires bravery. To place our flawed selves in

the context of this magnificent, broken world is the opposite

of narcissism, which is building a self-image that pleases you....”“Listen to me: It is not gauche to write about trauma. It is

subversive. The stigma of victimhood is a time worn tool of

oppressive powers to gaslight the people who they subjugate

into believing that by naming their disempowerment they are

being dramatic, whining, attention-grabbing, or beating a

dead horse. Believe me, I wish this horse was dead.”

Melissa Febos. “The Herat-Work: writing about trauma as a subversive act.”Febos’ essay in a recent Poets & Writers Magazine addresses several questions about memoir writing, especially ones written by women. In the 90’s the genre recreated itself out of the time honored literary tradition of the autobiography by focusing on an issue. Addiction as life history, usually to alcohol, drugs, sex or a combination of any or all three, replaced reflections on a glorious career. Books, often excellent ones, developed a pattern: I became addicted to____, degraded myself (I reveled in____/ wallowed in____) for 85 % of the book and overcame my addiction to write this book. By the millennium authors were becoming trapped as editors began looking for new and outlandish addiction stories to reveal. The genre was rapidly in danger of becoming a cliché.

Febos addresses this issue directly, as an author of a particular kind of addiction memoir; she was a former sex worker and drug abuse. This unapologetic book was followed by a recent collection of essays (or memoirs as she calls them), Abandon Me which reflects on her life after that book, Whip Smart. She does not regret having written the memoir and how it defined her, once, but she does object to being categorizing by it now. Imagine being a respected author, college lecturer, teacher of creative writing and being introduced as “Former Dominatrix and author.” Why, she demands, can I not be perceived as a person, a woman, as an equal being, who is much more than the sum of those long-discarded parts? She also demands: Why can’t a person reveal the most intimate traumas of her life to reveal who she has become now? Why not indeed? Febos insists: Trauma memoirs are not clichés. Pain cannot be quantified and is never a cliché.

Dickinson’s memoir encompasses aspects of the trauma memoir: she was raped while hitchhiking, was disfigured in an “accidental” shooting”, but she encompasses the trauma while working on a larger canvas: a family history that spans generations. The conceit of the book is Dickinson returns to her Iowa home to be with her mother, and two half-brothers (to whom the book is dedicated) in their mother’s final hours. During the death bed vigil, their mother acts as madeleine to reveal her personal history: her wild child days rebelling against all forms of authority, drinking, having sex, drugs use, and recklessly driving without a license in a way that caused fatal harm to others. She neglects her studies, blows off college to embark on one of these ill-fated hitchhiking experiences, and gradually comes of age severely damaged but knowing it is time to move on and move out.

All through this thoroughly engaging, expertly crafted, finally balanced memoir, we sense an authorial balance that has come to terms with her limitations and uses her mother’s final hours to find her place among her ancestral history. Readers of her fiction, poetry and essays will see how her life directly informs her creative work. Interested readers are encouraged to see her novel of the rape, Half-Girl, The Emily Fables, a prose poetic recreation of the inner life and times of her grandmother as well as life on the farm in rural Iowa at the turn of the last century and beyond, and her book of poetry, Corn Goddess. In fact, I would recommend all of her many, and varied books, from Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg, which I recently read for the second time, Lust Series, to the chilling noir, Love Highway, a murder story based on an actual event. This memoir re-enforces the idea that looking back with regret accomplishes nothing, but looking back, with a clear-eyed sense of self, is a form of moving on, damaged, perhaps, but as a more complete person.

Thaddeus Rutkowski, Guess and Check, Gival Press, www.givalpress.com, 237 pages, pb, $20, 2017.

The characters are familiar: the unnamed first-person narrator, his two younger siblings, a sister and a brother, his overbearing, obnoxious Polish father and his distant Chinese mother. Life is difficult for the first-born son. He is not popular at school. He is smart but tries not to act that way so he might fit in. He doesn’t fit in. The father is an artist, of some kind, who resents his son because he doesn’t look like him. In fact, the father despises all his children for their foreignness. For being biracial. No one loves the father. No one understand him. His life would be so much better if he did not have to earn a living and support all these ungrateful people. Mostly what he is doing is projecting his own alcohol fueled self-loathing on his children. The father seems intent on making his son in his own hateful image as a deluded, drunken, dissatisfied loser. And he is making real progress in that direction before being fatally stricken.

The attitude of the children towards the father, in previous books, was bemused and befuddled, bewildered and beleaguered, by his outrageous behaviors. Though the father occasionally tries to teach the children about nature and literature, it feels half-hearted and ill-conceived. There was always a sense of latent hostility that had not crossed over into outright abuse. In Guess and Check there is no ambiguity about the father. He physically abuses his daughter. Or so she says, and there is no real reason not to believe her. Likewise, he abuses and belittles the younger child. He verbally assaults and attacks the elder, the narrator, who does his best to adhere to his father’s impossible demands. But always fails.

Roughly one third of the collection of sixty-five scintillating stories proceeds this way. But these are not grim stories, as Rutkowski always manages to maintain a subtle balance between outright terror and put-upon youth. The narrator is something of a doofus but resourceful enough to persevere with a sense of humor. He is always someone who reacts rather than initiates. He prevails by persevering and moving onto the next stages of his life, taking what happens as it comes.

Rutkowski’s style seems relatively straightforward: simple sentences, in fact you would be hard pressed to find a compound sentence in the collection. He manages to present a first-person point of view that feels like an omniscient narrator, a third person seeing the first person through a refractive lens of irony. The surface reality seems to be the way the narrator describes it but actually it isn’t. This is an extraordinary accomplishment.

The remaining bulk of the collection details the narrator’s escape to college, time after spent bumming around Europe and in The City, followed by married life and parenting a daughter in New York. While Guess and Check is billed as a collection of stories you could just as easily describe it as an episodic novel in 65 vignettes. Or a fictional memoir. The narrative voice is so familiar, so intimate, it feels authentic enough to be “real”. As in, did you really do that at Cornell? Was your Dad really like that? Is any of this made up? Or is all of it made up? In the end, it doesn’t matter. What matter is, Guess and Check is a great read.Stephanie Emily Dickinson, The Emily Fables, ELJ Publications, www.eljpublications.com, 72 pages, $16.99, 2016.

In this brief but luminous book, Dickinson inhabit s a life. By inhabits, I mean, more than creating a life, she enters into it. She brings a world to the page and makes it breathe. Emily is the only girl in rural Iowa farming family at the end of the nineteenth century. Life is hardscrabble, at best. None of the amenities of daily life are available: the only constant, life, death, and hard work. Roles are clearly defined: men work the fields, preside over the household, and women tend to the household, have children, cook, wash, clean, and all else that needs to be done. There is no time or energy for frivolities such as nurturing, learning, or socializing. Despite the limited horizons, it is a loving family, as Emily is clearly her father’s favorite.

The spare, evocative, almost elegiac, tone of the language creates a painter’s landscape to the fables. And they are fables. Each, at most two pages, is self-contained, has an immediate specificity and resolution, not so much a moral, but a resolution the way poems do. In fact, these feel like finely crafted prose poems, part of a sequence where each part fits into the puzzle of a life. The book has the range and depth of a prose novella and the resonance of poetry.

Each of the three sections represent stages of life. The first is both joyous and haunted. Childhood has the magic of discovery but the omnipresent specter of imminent death. There are no traveling doctors or hospitals for children afflicted by diseases inoculations mostly prevent completely now. Emily’s best friend is taken at age eight by “The Strangling Angel”, diphtheria. An extended family of classmates contracts whopping cough and most die of the wasting disease bearing the mark of blood apples from their ravaged lungs. Emily contract Scarlet Fever but survives. The scourges are many, the release, final.

Despite an uncommon, perhaps prodigal gift for learning, Emily is denied education beyond the eighth grade. A girl acquiring book learning beyond this point is considered wasteful. Despite an almost lustful craving for knowledge Emily is denied this right. Her role is to be a wife, a mother, and a matriarch, in the mold of her forbearers. She marries at sixteen. Begins child bearing not long after.

The second chapter of her life is marked by the general waning of the enthusiasm of life that the Emily of part one so revels in. She has a happy marriage, to a good man, whom she loves and cherishes, but the work is hard and stifling. The agonies are many, but none more poignant than the seven-day baby. Dickinson devotes three pieces to her grief, her reluctance, to let go and then the subsequent funeral of the infant. So profound is her loss, she renounces sex with her husband to avoid a further child bearing to fill a grave.

The final, all too brief section, is Emily in her mature years reflecting and interacting with the family. A simple-minded sister in law, her delirious mother-in-law in a sickroom, the almost feral neighbors, a mother and daughter sickened by grief and loss of young man in World War I. This section feels like a fever dream, entering and leaving consciousness where the dreams and daily life become so intertwined it is almost impossible to separate the two. Life is terrifying in its ordinariness as it is for the potential for cruelty. The death of her son’s dog, set on fire for no real reason, is terrifying in its immediacy and for the evocative power of the images. Somehow, we survive even this, the apparition, The Depression, the wandering homeless hobos arising out of the darkness, the woods like fairy tale ogres. It is what we do: survive. These stories all inter-connect, have the feel of an actual history mined for its details and transformed into Art. Actual or imagined? In the end, there is no difference. Emily’s fables are our own.