A Review/Appreciation of Alexandra Van De Kamp by Alan Catlin

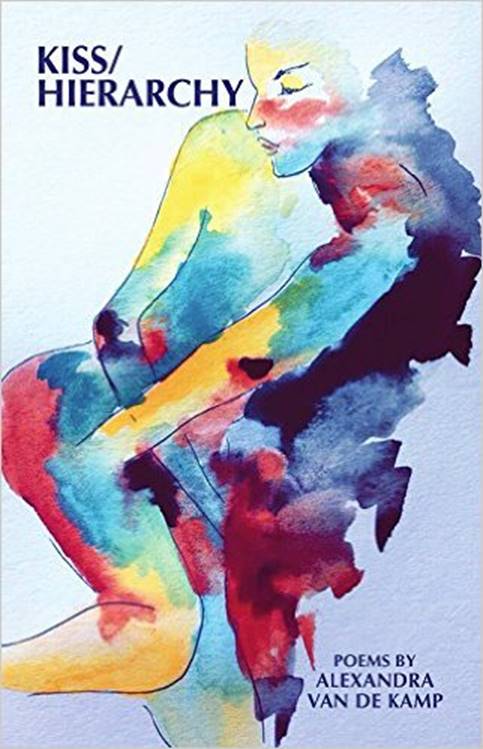

Alexandra van de Kamp, Kiss/Hierarchy, Rain Mountain Press,

rainmountainpress.com, 87 pages, $16., August 2016.Kiss/Hierarchy: an appreciation

“I would say film directors have it made

they place a filter over the lives and viola!

their world is transformed into a coppery,

late October glow. I’ve often wished

I could do that in a poem.”

from “Dear V-“1-

The feeling is as if you are on the way to an endless vacation, maybe like a Lost Weekend or just an ordinary weekend. Maybe you become stuck in the longest panning shot ever, the traffic accident to end all traffic accidents, than a real life incident. And you realize that what has happened is that you are involved in something that is a metaphor of modern consumerism like, say, Warhol’s Green Car Crash (Green Car Burning1), which is just modern life taken from the pages of the newspaper. On one level, anyway. There may be a difference between metaphor and reality, but who knows what it is anymore?

Maybe the traffic problem is more like a Cortazar story where everyone is stuck on the pavement, waiting for something to come unstuck, and no one knows what they delay is, or when it will end. This, before cell phones, but could cell phones change the way life is, once highways have achieved maximum capacity, and eternal gridlock? Or maybe, it is like the opening passages of Pynchon’s V, where he describes Long Island traffic as a kind of urban hell and anyone who has been there knows that it is exactly what it would look like, does look like, and nothing short of the heat death of the planet was ever going to change the scene.

All the while you are traveling in this story, the vision outside shifts, from concrete and spontaneous car ports, to beach scenes, where loungers sit on canvas back chairs looking out at a perfect, static sea. The setting is some place like the Cape, though it could be anywhere that sand and sea come together. The recliners seem rooted, moored, like land creatures in an Edwin Hopper dream, instead of people, creatures who once lived in beach houses that do not conform to the physical dimensions of any know world.

But instead of on-a-beach, you find yourself in an old world hotel, one with geometrically perfect topiary gardens and mazes, all perfectly trimmed to exactly the same height, as if modeled on ones used in the set of “Last Year in Marienbad” but in color now. This is a place where time has no meaning, where scenes from other places can be perfectly re-created, though no matter how much everything appears the same, they are all different in some meaningful way. No matter how you look at the hotel, what you do after being there, your name has been entered into the register and cannot be removed. When all is revealed, you will not be surprised to learn the hotel is as dead as the people inside it, are lost in memory of an uncertain time that may never actually have existed.

2-

After the holiday, there is another hotel you must visit, in a place that could be a watercolor of Vienna at night in the rain. The poorly lighted exterior sign says: Alexandra’s, which means nothing to you until you have settled inside. The workers behind reception are the gangsters who claim they are the two men who moved the body of Harry Lime from the road after he was struck and killed by a car. Later, Orson Welles will appear as the stranger from another movie, on another continent, whose life ends ironically, and in a bizarre manner. Everyone who sees the impaled body of the pursued, revolving on a replica old world clock- tower’s figurine, will never forget. Everyone will be left as breathless as a blonde in the front seat of a joy ridden stolen car with a man driving whose future is as final as a gunshot in the street that only a fleeing man could stop.

3-

All the rooms in the hotel are like the ones Anthony Perkins lives in as K in The Trial: disproportionate and viewed only at odd angles. The impossible doors admit strangers with weapons acting as officers of the court, whose explanations of why they were there, would be surrealistic as poems if their words contained any sense. Escaping into the lobby reveals a Grand Hotel in decline with all of the usual suspects in attendance.

In the locked room next door to the lounge, a wedding reception is taking place. All the melancholics have exchanged rings, favors, and vows, making toasts, though the pact sealing kiss exchanged, is not a kiss at all. The lavish feast after, is part Breughel, part von Trier, part Resnais, as the re-created perfect garden waits outside the Dutch doors to be seen. When the champagne glasses of the betrothed touch, time stops, and everything becomes like a beautiful movie about the end of the world that looks and sounds much better than it actually is.4-

When time resumes, the scene is a close up of a Cornell Box as filmed by David Lynch at the opening of a new movie. Gradually, the handheld camera backs away from the tableau. Which movie is it? Or, should we ask, which Cornell box?

Then we are in an installation by Dali in the 1939 World’s Fair, sitting as a passenger in a yellow cab, amid an overgrowth of vegetation, urban decay, and weeds with two shriveling, dead human bodies. Think of this as that scene in “Silence of the Lambs” where Agent Starling is following a lead offered by Dr. Lechter, searching for a death watch beetle clue. Think of the “Thin Man”, think of Humphrey Bogart and the stuff that dreams are made of. van de Kamp’s book is like that only much, much better.